Evo Italian Restaurant

- 561-745-2444

- email us

- Jupiter, Florida, United States

JUPITER, FL – November 3, 2017 – In early 1986, I started working as an Ocean Lifeguard for Palm Beach County, Florida. Quite often, my assignment was at Carlin Park in Jupiter. On busy days, there were only two guards assigned to monitor beachgoers from the Carlin lifeguard tower, the one lifeguard tower on the south end. The tower was a wooden structure, with a long gradual ramp towards the beach. We were constantly pounding down nails that popped up, so we wouldn’t cut our feet. Rescues were made, sometimes starting with a full run from the top of the ramp.

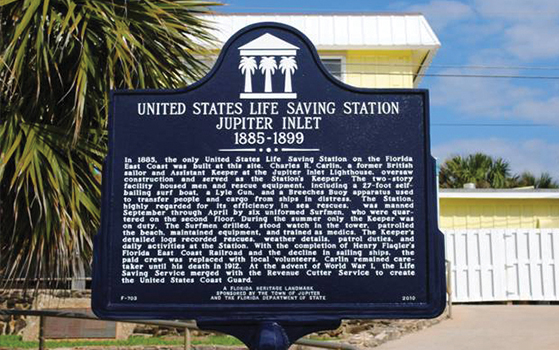

Approximately 100 years before I was hired, the United States Life-Saving Service (USLSS) had built a lifesaving station near there to respond to vessels in distress near the inlet. On one of the memorial signs placed by the Seminole Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, the names of the “gallant” men who worked at the Jupiter Inlet Station are listed.

The Surfmen

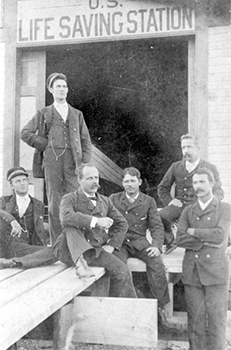

Who were these men and how did they go about their work at Jupiter Inlet in the late 1800’s? Those named on the sign are: Captain Charles R. Carlin, John H. Grant, Charles W. Carlin, Harry Dubois, Graham King, Daniel Ross, and Fred Powell. Some others who served are Henry Archibald (who became station keeper at Indian River and Bethel), Nelson Cowles, and Tom Mitchell. Here are a few brief biographies.

Captain Carlin was born in 1842 in Dublin, Ireland to English parents. He served in the British Navy before coming to Florida to be a geodetic surveyor. He served as assistant lighthouse keeper at the nearby Jupiter Lighthouse, and in 1885 was named Captain (sometimes referred to as “Keeper”) of the USLSS station. Carlin Park is named after Captain Carlin.

Surfman Henry “Harry” DuBois was a member of a pioneer family which had built a home at Jupiter Inlet on top of an ancient Indian shell mound. The restored house is still on the site and a county park surrounds it named DuBois Park. Harry also worked in the pineapple and beekeeping businesses.

Surfman John Grant served as postmaster and mailman in Hobe Sound. Graham King was Captain Carlin’s son in law. Charles Wesley Carlin was Captain Carlin’s son.

Captain Charles Robert Carlin

The Station

The lifesaving station was a two-story structure built on a bluff a mile south of the Jupiter Inlet, with a four-sided lookout tower on the roof, where there were signal flags and a powerful spyglass mounted on a tripod. On the ground floor was a cloak room, a utility room, and a self-bailing lifeboat mounted on a wagon on top of a wooden ramp that led down to the beach. The second floor contained the crew’s quarters, iron cots, and lockers.

At the time that the Jupiter Inlet station was in operation, the inlet was natural—it shoaled and changed course. The Loxahatchee River (which fed the inlet) emptied into the Atlantic Ocean as far south as the current Jupiter Beach Resort.

Starting on September 1, 1886, Captain Carlin supervised six paid Surfmen from roughly September through May each year, while serving alone during the summer when the ocean was generally calmer. A report from 1896 stated that the Captain’s salary was $2,000/year, while the Surfmen were paid $60-65/month.

There were six-hour shifts, with one Surfman in the tower, one Surfman patrolling the beach to the south, and another to the north. The Surfman drilled regularly, including practice with a Lyle gun and a breeches buoy apparatus.

Surfmen (from left to right); Graham W. King, Sr., Charlie W. Carlin (standing), John Grant, Dan Ross, Tom Mitchell, and Henry “Harry” DuBois (arms folded)

The rescues

The following are three selected (verbatim) entries from the 1890’s:

April 3, 1896 – American schooner Belle – About 3:30 A.M. the patrolman was hailed from a small schooner, which had anchored the preceding evening near the station, on the edge of the Breakers. Being unable to understand them, the patrolman swam off to the vessel and ascertained that her crew of two men were desirous of beaching her. He warned them against so doing, and returning ashore reported the matter to the keeper. As the sea was making, and the wind gathering force, the keeper sent Surfmen Nos. 1 and 4 on board, with instructions to carry her to Lake Worth. The surf was now breaking over the schooner, and finding her crew demoralized, the life-savers slipped the cables and stood offshore in a heavy sea and half a gale of wind. The vessel was unable to stand the force of the waves even when hove to, so they were compelled to scud, which carried them past Lake Worth before daylight, and determined them to hold their course for New River Inlet, 60 miles south of Jupiter, where they crossed the bar in safety, and beat up to Fort Lauderdale House of Refuge, reaching there at 3:30 P.M. There, they left the vessel in charge of the keeper, who took them two miles in his boat to the railroad station, and furnished them with funds to carry them home, where they arrived at 10 A.M., April 4.

February 9, 1892 – Medical aid given – Word having been received that a man had accidentally shot himself, the keeper hastened to carry necessary medicines and bandages with which the wound was properly dressed.

February 6, 1895 – Rescue from drowning – A young man with a party of friends went into the surf near the station. Being unable to swim, the keeper loaned him a life preserver, but he was nevertheless carried out by the undertow and was in danger of being overcome and drowned in the rough water, when Surfman Charles M. (sic) Carlin heroically swam out to his relief and assisted him ashore. This action was very bold, and resulted in saving the imperiled bather’s life.

United States Life-Saving Station, Jupiter Inlet 1890s (left) and after the 1900s (right)

Decommissioning

No Surfmen were employed after 1896. Captain Carlin remained employed, recruiting volunteers during emergencies. The USLSS at Jupiter Inlet was decommissioned January 21, 1899. Captain Carlin died in 1912 from injuries incurred while trying to save the remnant life saving station from a brush fire.

The Shifting Sands

Well over 100 years have passed since the Jupiter Inlet station was decommissioned. One day, I decided to find the spot where it was built. USLSS records many times referred to it being located one mile south of the Jupiter Inlet at Latitude 26 55 30 North, and 80 04 00 West, and built, “on a bluff for good viewing.” I started at a sign in front of the Lazy Loggerhead Restaurant near the main parking lot in Carlin Park which states that the Station “was built at this site.”

Florida Heritage Landmark sign at Carlin Park sponsored by the Town of Jupiter and The Florida Department of State

Standing by this sign, I opened my compass app on my smart phone. The compass includes coordinates in degrees, minutes, and seconds. My reading here was: Latitude 26 55 47 North, Longitude

80 04 06 West. Since latitude is measured north of the equator, I was 17 seconds north of the former station coordinate, and six seconds west of the longitude coordinate. I started walking south on the Carlin Park road with my smart phone. I left the park road near the current Carlin south lifeguard tower, and continued south along the sidewalk on A1A. Very close to the southern boundary of Carlin Park, and near Beach Access #57, my compass equaled the published Station Latitude of 26 55 30 North. My longitude reading here was 80 04 03 West. So I turned east, walked down the Beach Access #57 stairs to the beach and walked directly to the shoreline near high tide. My final reading here was: Latitude 26 55 30 North, Longitude 80 04 02 West (very close here to the desired location, only two seconds west of where I was seeking). I was approximately .35 miles south of my starting point at the historical marker sign. two seconds of longitude at this latitude is roughly 50 meters. The Jupiter Inlet Life Saving Station in 1886 was built in a location that is now underwater!

Sources:

United States Life Saving Services Annual Reports (United States Coast Guard Records).

“Five Thousand Years on the Loxahatchee”, by James D. Snyder.

Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse and Museum, Josh Liller - Historian and Collections Manager.

This article originally appeared in American Lifeguard Magazine in a different form.