Melissa Odabash

- 44 207 499 9129

- email us

- London, West Sussex, United Kingdom

JUPITER, FL – April 26, 2017 – “Lighthouse keeper” might conjure up images of an old sea captain and his family on a remote wind-swept bluff or rocky island in New England, the light in their little tower and attached home remote yet cozy. There is some truth in that stereotype, but it doesn’t capture the scope of being a lighthouse keeper in places as diverse as Alaska, Hawaii, Maine, and Florida.

The beam from Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse began to sweep the horizon in July 1860. Our area was a wilderness, with no permanent settlers between the Fort Pierce area and Miami. There were no reliable roads to Jupiter, no railroad, and no direct communication with the outside world except signaling passing ships or sailing up the Indian River. Jupiter Inlet itself was incredibly fickle: Usually shallow and often closed. The government struggled to find the earliest keepers for the remote location and none lasted very long before the Civil War intervened. Confederate sympathizers from Fort Pierce (one of them a disgruntled assistant keeper) put the lighthouse out of service in August 1861, sending the head keeper and his family packing back to Key West in a small boat with few provisions.

When the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse returned to service in 1866, some stability finally arrived. James Armour was one of the new assistant keepers and a few years later earned a promotion to head keeper. He remained at the lighthouse for 40 years. Capt. Armour was a constant during Jupiter’s early pioneer era. Tourists and other pioneers appreciated his calm demeanor and hospitality, and he was friendly with Seminoles who visited or lived in the area. Armour raised a family in a howling wilderness so rural that an infant daughter died before she could be brought to the nearest doctor and he once had to shoot a Florida panther that was raiding the family’s chicken coop. Armour’s assistants were mostly pioneers themselves, including seven of his wife’s relatives. Some used their spare time to build boats, while others saved up money to homestead on the Indian River or around Lake Worth.

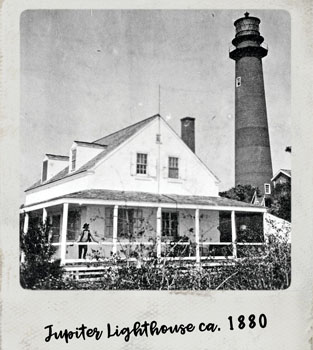

This photo, taken by Assistant Keeper Melville Spencer ca. 1880 shows Captain Armour on the porch of the keepers’ house.

One of the longer serving pioneer assistant keepers, Melville Spencer, captured remarkable images of tourists, Seminoles, steamboats, wildlife, and other local scenes with his camera. Selling the photos in stereoview form, Spencer’s images capture a Florida that residents today would find almost unrecognizable. Hannibal Pierce was another notable pioneer assistant. He worked at the lighthouse for a year before homesteading on Hypoluxo Island. His son, Charlie, wrote an important memoir, Pioneer Life In Southeast Florida, and is the subject of an award-winning series of children’s books, The Adventures of Charlie Pierce, written by Harvey Oyer III, a descendent of Charlie’s sister.

Civil Service Reform and the arrival of Flagler’s railroad in the 1890s marked a shift in lighthouse keeping. Many of the early 1900s keepers were career keepers, working for decades at different lighthouses as they sought promotions or transfers to more desirable stations. Capt. Armour was succeeded by his son-in-law, Joseph Wells, who was frequently praised for his efficiency and outstanding work. Persistent health problems cut Wells’ career short after about 25 years as a keeper (13 as head keeper). Charles Seabrook became the final civilian head keeper at Jupiter, serving 27 years until his retirement in 1946. He witnessed powerful hurricanes, a fire that destroyed one of the keepers’ houses, the arrival of electricity, the lighthouse service’s merger with the Coast Guard, and World War II. After Seabrook’s departure, a series of Coast Guard enlisted personnel served as keepers until the lighthouse was automated in 1987.

Until Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse was electrified in 1928, keepers had the daily task of carrying a two- to-three gallon can of fuel (weighing about 30 lbs.) up the 105 stairs to fuel the lamp. The lamp had to be lit by hand shortly before sunset and extinguished shortly after sunrise. It would also be lit during storms. The lamp had five concentric wicks, which had to be trimmed periodically to ensure they burned evenly. A glass chimney that helped send the smoke through a vent in the ceiling had to be monitored and handled carefully to avoid breakage or damage from the heat of the lamp. To turn the lens the keeper used a hand crank to wind up a heavy weight. The descending weight unspooled a cable connected to a system of clockwork that turned the heavy Fresnel lens, creating the bright beams of light. (The system was not unlike an elaborate grandfather clock.) Keepers also had to keep watch for passing ships, especially those in distress. Keepers maintained various logbooks of station activities, passing ships, and use of government supplies. When supplies were delivered the keepers had to pitch in to unload them from the government lighthouse tender. This included carrying a year’s supply of fuel cans up the hill to the Oil House. When the Jupiter Inlet closed, supplies would be delivered on the beach and the keepers had to retrieve them before high tide or bad weather ruined them.

RELATED Rare Fish Congregating Off Jupiter, Stoked for the Cause , Submerged, A Heroic Act

Electricity brought two major changes to lighthouse operations: A 1/3 horsepower motor rotated the lens (replacing the clockwork and weight) and light bulbs replaced the oil lamp. If commercial power failed the keepers would fire up a diesel generator to keep the light shining. The generator failed on a few occasions during which time the lens was turned by hand with a temporary kerosene lamp in place. Electricity also brought the installation of a radio beacon at the light station that broadcast the Morse code letter “J” as an aid to navigation. The keepers were responsible for making sure the beacon broadcast on schedule and also monitored the signals from other lighthouse radio beacons to ensure they were also broadcasting on schedule too. By the 1950s, the radio beacon was operating around the clock and had to be constantly monitored by the Coast Guard keepers. The transmitters and timers were prone to malfunctions, especially from nearby lightning strikes.

For major construction projects, the lighthouse service would dispatch a work crew, but day-to-day maintenance was the responsibility of the keepers. They had to clean the glass, inside and out, of both the Fresnel lens itself and the lantern glass. A Fresnel lens is made of special glass and has to be cleaned with great care to avoid damage. Keepers also had to repair any rust on the ironwork, clean the interior of the lighthouse tower, oil the clockwork and motor, check the rotation of the lens, and periodically paint the exterior and interior of the brick tower. Painting the exterior was an especially dangerous task with the keepers working from a hanging scaffold. Thanks to the diligent work of the keepers, nearly all of Jupiter’s original brickwork and ironwork have survived to the present day. Jupiter also has one of only 13 remaining active first-order Fresnel lenses (the largest kind) in the entire United States.

The lighthouse was not the keepers’ only responsibility. The houses, outbuildings, and grounds of the light station all had to be kept neat. A lighthouse inspector visited quarterly and failure to keep the entire station in good condition could lead to dismissal. The keepers’ families would help with the housekeeping, especially frantic last minute work when the inspector’s ship was sighted approaching offshore.

During the civilian era, Jupiter had three lighthouse keepers at a time. After World War II, the Coast Guard added a fourth keeper through at least the 1970s. All told, more than 70 civilians served as keepers or caretakers of Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse between 1860 and 1939. More than 100 military keepers served between 1939 and 1987.

To learn more about the lighthouse and walk in the footsteps of its keepers, please visit the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse and Museum, including our new exhibit, “Keeping The Light At Jupiter Inlet.” The lighthouse and museum are open every day except Monday from 10am to 5pm, with the last lighthouse tour starting at 4pm. Visit our website www.jupiterlighthouse.org for more information, including a calendar of events and information about how you can support the lighthouse.

| LOXAHATCHEE RIVER HISTORICAL SOCIETY: THE FIRST KEEPER

|

|---|